In the First Meditation of That All Shall Be Saved, David Bentley Hart presents the primary argument of the book, his “moral modal” argument for universal salvation. It purports to prove that the traditional concept of Hell is logically incompatible with classical theism. It is surprising, then, that the argument has been largely ignored by the book’s critics. Benjamin Guyer, Edward Feser, Denys Kondyuk, Joshua R. Brotherton, and Taylor Patrick O’Neill neglect it entirely;1 Alan Gomes, Benjamin DeVan, and James Dominic Rooney mention it in passing but give no response;2 and Michael McClymond and Douglas Farrow make an inadequate criticism based on a cursory reading.3 Even Mats Wahlberg, who spends several pages quoting and paraphrasing parts of the First Meditation, does not actually engage with it.4 Thus, despite the attention the book has received, its primary argument remains unanswered.

Hart, of course, thinks it is unanswerable: “It is a demonstration that can be supplemented and enlarged, but I do not believe it can be refuted.”5 Hence, “anyone who remains unpersuaded by it has simply failed to understand it.”6 As the book’s author, he is willing to bear some of the blame for this: “I could have written the text in a more propositional form,”7 but he also thinks his readers must share the responsibility:

understanding is always a collaboration. Both sides have to do their parts. Even the clearest of texts has to be met at least half way by the good intentions of the reader, but even a reader’s purest intentions can be thwarted by a text that presumes premises with which he or she is unfamiliar. And I have discovered that the parts of the book’s argument for which some readers have proved especially unprepared are found in its First and Fourth Meditations.8

Perhaps this is right. Or perhaps the First Meditation is more difficult than Hart realizes. Whatever the case, his argument has not been understood, and as a result, it has not been adequately addressed. This is an unhappy state of affairs, but it is also a fixable one. The conversation could still be salvaged. If the argument, including some of its presumed premises, were stated in a propositional form, the book’s critics would understand it. They would then be obliged to respond. Hart might reply, after which there might even be further replies. All of this would be for the best. The argument needs a proper vetting. Only by appraising informed attempts to refute it can we evaluate Hart’s claim that it is irrefutable.

One might expect Hart to restart this conversation with a step-by-step guide, but he has not.9 No doubt, the idea of setting aside his “predilection for writing prose rather than bullet-points”10 offends his aesthetic sensibilities. Others have tried to help out, but with limited success.11 So there is still need for a simple but detailed exposition. The following is an attempt to meet that need. Section I works through some relevant passages of the First Meditation and, along the way, reconstructs the bulk of the argument in a propositional form. Section II explains Hart’s use of game theory in the last part of the argument. Section III briefly examines some presumed premises. And Section IV takes a very quick look at a greater good response.

I. Intending the Éschaton

The best place to begin is with an early remark about ends:

In the end of all things is their beginning, and only from the perspective of the end can one know what they are, why they have been made, and who the God is who has called them forth from nothingness. Anything willingly done is done toward an end; and anything done toward an end is defined by that end. (68)

Notice the multivalent use of “end”. In the first sentence, it means an ending, in contrast to a beginning. It is a terminus, a térma. Furthermore, as the terminal state of all things, it is the novissima, the éschaton. In the second sentence, “end” means a goal, that toward which something is done. It is a finis, a télos. While these distinctions can be gathered from the context, the repetition of “end” tends to blur them. This is likely deliberate. For it suggests that the télos of creation and the éschaton are the same, which is a central premise of Hart’s argument.

That premise is implied in the passage above: “only from the perspective of the end can one know . . . why [everything has] been made,” and in Hart’s endorsement of Gregory of Nyssa: “the cosmos will have been truly created only when it reaches its consummation in ‘the union of all things with the first Good’” (68). But he makes it explicit at the end of the next paragraph:

the end toward which [God] acts must be his own goodness; for he is himself the beginning and end of all things. This is not to deny that, in addition to the “primary causality” of God’s act of creation, there are innumerable forms of “secondary causality” operative within the created order; but none of these can exceed or escape the one end toward which the first cause directs all things. And this eternal teleology that ultimately governs every action in creation, viewed from the vantage of history, takes the form of a cosmic eschatology. Seen as an eternal act of God, creation’s term is the divine nature for which all things were made; seen from within the orientation of time, its term is the “final judgment” that brings all things to their true conclusion. (69)

In the third sentence, Hart identifies the télos of God’s creative act with the éschaton. In the fourth, he elaborates by identifying both with the térma of God’s creative act: “creation’s term is the divine nature for which all things were made”; and creation’s “term is the ‘final judgment’ that brings all things to their true conclusion.” That is,

The térma of God’s creative act is its télos.

The térma of God’s creative act is the éschaton.

Therefore,

the télos of God’s creative act is the éschaton.

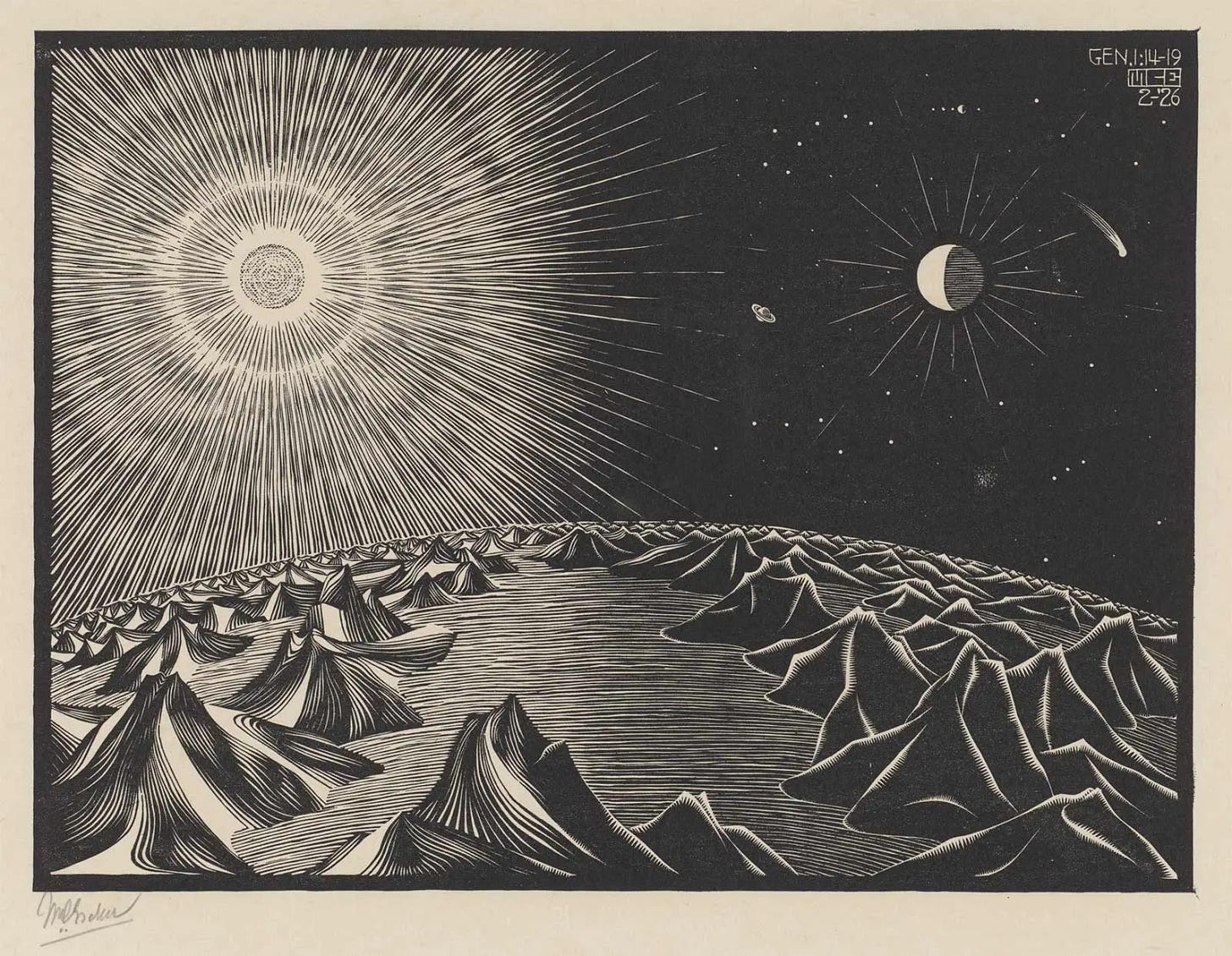

These remarks about ends are intertwined with Hart’s discussion of another central premise, the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo. Following Gregory, he holds that this doctrine is “not merely a cosmological or metaphysical claim, but also an eschatological claim about the world’s relation to God” (68). Just before identifying God’s creative télos with the éschaton, he explains that “the doctrine in itself is, after all, chiefly an affirmation of God’s absolute dispositive liberty in all his acts – the absence, that is, of any external restraint upon or necessity behind every action of his will” (69). Thus, “God’s act of creation is free, constrained by neither necessity nor ignorance” (70). Contrast this with human acts of making. A potter is neither omnipotent nor omniscient. Consequently, the térma and télos of his potting can come apart: he can make a flawed pot. God, on the other hand, cannot make a flawed cosmos. In his omnipotence and omniscience, He cannot fail to accomplish his goal—the térma of His creating must be its télos. Accordingly, the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo entails the first premise above.

God’s creative act is free of every limitation.

If a creative act is free of every limitation, its térma is its télos.

Therefore,

the térma of God’s creative act is its télos.

And in combination with the first argument above, the doctrine entails the identity of God’s creative télos with the éschaton. In this way, it is “an eschatological claim about the world’s relation to God.” Because His act is free, He creates in order to bring about the final state of all things.

With the foregoing in view, the first steps of the moral modal argument can be reconstructed as follows.

1 God’s creative act is free of every limitation.

2 If a creative act is free of every limitation, its térma is its télos.

3 The térma of God’s creative act is its télos.

4 The térma of God’s creative act is the éschaton.

5 The télos of God’s creative act is the éschaton.

Proposition 1 follows from the classical conception of God as omniscient and omnipotent; P2 follows from the “logic of acts” (see Section III); P3 follows from P1 and P2; P4 follows from the classical conception of God as eternal (see Section III); and P5 follows from P3 and P4.

The next trio of premises concerns God’s creative intention.

6 The télos of an act is intended by the actor.

7 The télos of God’s creative act is intended by God.

8 The éschaton is intended by God.

P6 is true by definition: the goal of an act is what is aimed at, the intended outcome; P7 follows from P6; and P8 follows from P5 and P7. Hart touches on this part of the argument in the next paragraph.

[A]s God’s act of creation is free, constrained by neither necessity nor ignorance, all contingent ends are intentionally enfolded within his decision . . . One way or another, after all, all causes are logically reducible to their first cause. This is no more than a logical truism. And it does not matter whether one construes the relation between primary and secondary causality as one of total determinism or as one of utter indeterminacy, for in either case all “consequents” are – either as actualities or merely as possibilities – contingent upon their primordial “antecedent,” apart from which they could not exist. And naturally, the rationale of the first cause – its “definition,” in the most etymologically exact meaning of that term – is the final cause that prompts it, the end toward which it acts. If, then, that first cause is an infinitely free act emerging from an infinite wisdom, all those consequences are intentionally entailed – again, either as actualities or as possibilities – within that first act; and so the final end to which that act tends is its whole moral truth. (70)

Hart’s talk of “all contingent ends” might lead some to suppose that, on his view, God intends every historical event, including every evil. But this obviously contradicts what he goes on to say about God, namely, that, as the Good itself, He cannot intend any evil (see 70-71; cf. 90). A better interpretation reads “contingent ends” in its immediate context. Two sentences prior, Hart says that “the ‘final judgment’ . . . brings all things to their true conclusion,” i.e. their ultimate térma. These térmata are the “ends” in question.12 And for Hart, they are intended by God because “all causes are logically reducible to their first cause” and the first cause is defined by “the end toward which it acts.” As he later puts it, “the issue is the reducibility of all causes to their first cause, and the determination of the first cause by the final” (89). In other words, all secondary causes exist for the sake of the télos of God’s creative act; and since this is the “final end,” everything is created for the sake of its part in the éschaton. (This is just another way of expressing Propositions 3-5). Therefore, God intends the final state of all things.

It follows from all of this that, if the éschaton were to include a single suffering soul, then that suffering would be intended by God. But, as the Good itself, God cannot be evil. And it is evil to intend suffering. Hence, God cannot intend any suffering. Therefore, the éschaton cannot include a single suffering soul.

The eternal perdition – the eternal suffering – of any soul would be an abominable tragedy, and therefore a profound natural evil . . . A natural evil, however, becomes a moral evil precisely to the degree that it is the positive intention, even if only conditionally, of a rational will. God could not, then, intend a soul’s ultimate destruction, or even intend that a soul bring about its own destruction, without positively willing the evil end as an evil end; such an end could not possibly be comprised within the ends purposed by a truly good will . . . Yet, if both the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo and that of eternal damnation are true, that very evil is already comprised within the positive intentions and dispositions of God. (82)

Thus,

9 God is the Good itself.

10 The Good itself cannot be evil.

11 God cannot be evil.

12 It is evil to intend evil.

13 Suffering is evil.

14 God cannot intend suffering.

15 If there were any suffering in the éschaton, it would be intended by God.

16 There cannot be any suffering in the éschaton.

P9 is part of the classical conception of God. P10 is true by definition; P11 follows from P9 and P10; P12 is an application of the Thomist principle of moral specification: the moral status of an intention is determined by its object; P13 is also true by definition: suffering (as malum poenae) is a privation of some good; P14 follows from P11, P12, and P13; P15 follows from P8; and P16 follows from P14 and P15.

Finally, by similar reasoning, Hart argues that the annihilation of any person is also impossible.

The ultimate absence of a certain number of created rational natures would still be a kind of last end inscribed in God’s eternity, a measure of failure or loss forever preserved within the totality of the tale of divine victory. If what is lost is lost finally and absolutely, then whatever remains, however glorious, is the residue of an unresolved and no less ultimate tragedy, and so could constitute only a contingent and relative “happy ending.” (87)

The final loss of anyone would also be an abominable tragedy, and therefore a profound natural evil. So, it cannot be intended by God.

13* Annihilation is evil.

14* God cannot intend annihilation.

15* If there were any annihilation in the éschaton, it would be intended by God.

16* There cannot be any annihilation in the éschaton.

II. God Does Not Play Dice

At this point, someone might notice that the accepted distinction between God’s antecedent and consequent will has not been drawn. And he might think that, once it has, Hart’s argument is defeated.

God does not intend the éschaton come what may. Rather, of the many possible éschata, he intends only one, namely, the one in which all are saved. Every other éschaton, in which some end up suffering eternally, is merely permitted by God.

According to Hart, this move will not work because the distinction—between God’s intention and permission, or between his antecedent and consequent will—is inapplicable to the éschaton. If God freely creates the world from nothing, then every possible final state is accepted and therefore positively willed. Hart makes this case with a bit of game theory:

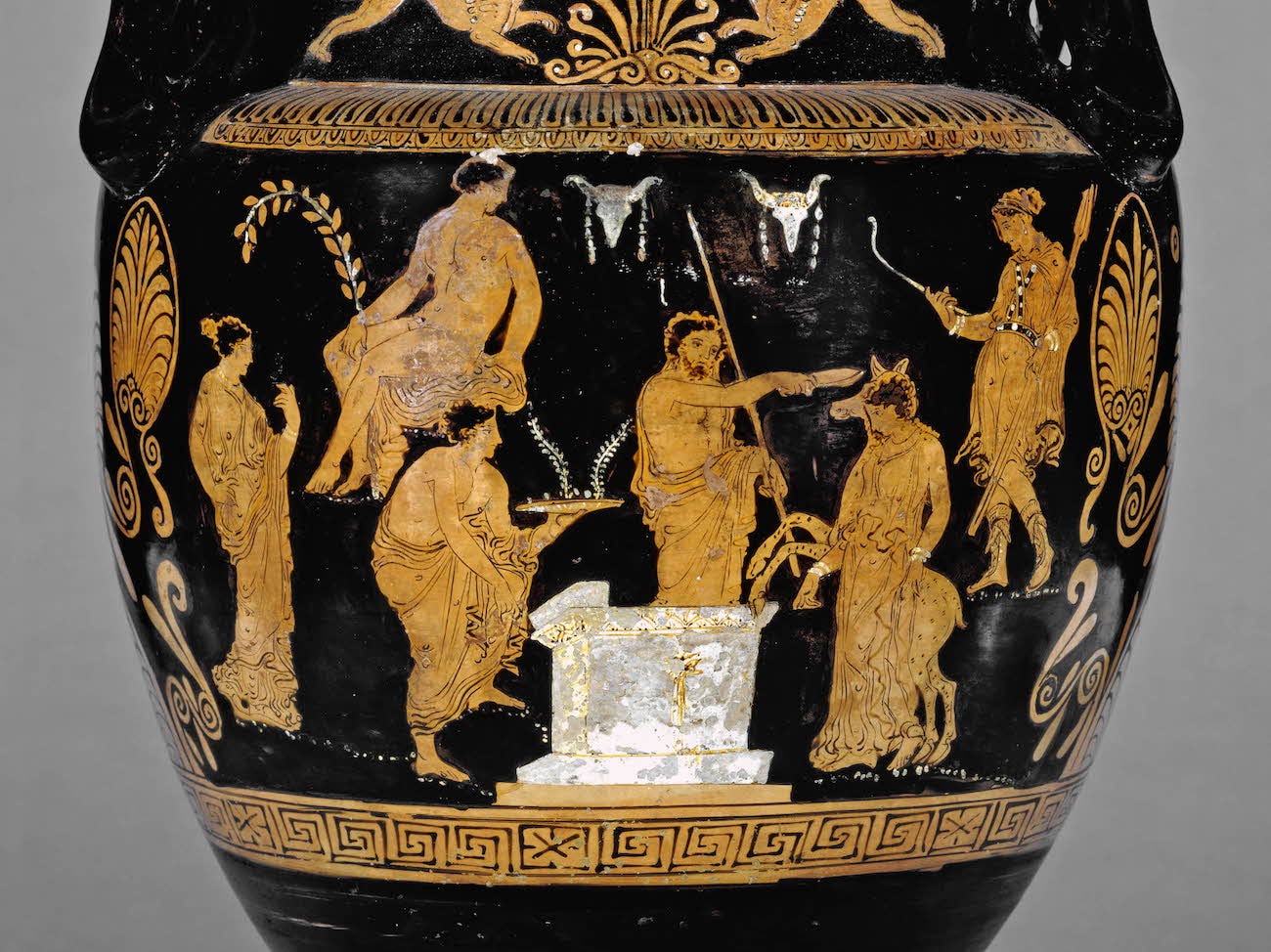

Let us, that is, say God created simply on the chance that humanity might sin, and on the chance that a certain number of incorrigibly wicked souls might plunge themselves into the fiery abyss forever. This still means that, morally, he has purchased the revelation of his power in creation by the same horrendous price – even if, in the end, no one at all should happen to be damned. The logic is irresistible. God creates. The die is cast. Alea iacta est. But then again, as Mallarmé says, “Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard” (A throw of the dice will never abolish the hazard): for what is hazarded has already been surrendered, entirely, no matter how the dice may fall. The outcome of the aleatory venture may be intentionally indeterminate, but the wager itself is an irrevocable intentional decision, wherein every possible cost has already been accepted; the irrecuperable expenditure has been offered even if, happily, it is never actually lost, and so the moral nature of the act is the same in either case. To venture the life of your child for some other end is, morally, already to have killed your child, even if at the last moment Artemis or Heracles or the Angel of the LORD should stay your hand. (86)

Consider Agamemnon. Even though he hopes that the goddess will change her mind, his decision to go through with the expedition is a decision to risk his daughter’s life. This is more than permission. In risking her life, he has accepted her death. Thus, whether it comes to pass or not, morally, he has already killed her. What is true of Agamemnon is, mutatis mutandis, true of a gambling God. Even though he desires that everyone will persist in union with him, (on the traditional view) his decision to create free persons is a decision to risk their immortal souls. This too is more than permission. In risking their souls, he has accepted their eternal suffering. Thus, whether it comes to pass or not, morally, he has positively willed that suffering. It follows that, at the eschatological horizon, there is a “moral modal collapse” of the distinction between God’s antecedent and consequent will.

Some of Hart’s critics—those who focus exclusively on this part of the argument—think they see a problem. If every possible cost is accepted, then God positively wills “the transient torments of history” (83). But that is something he cannot do. Hart, it seems, has managed to end up on the wrong side of the Problem of Evil. Thus, McClymond: “Hart’s ‘responsible Creator argument’ proves too much, for if God is morally responsible for eschatological outcomes, then why is God not also responsible for historical evils?” And Farrow: “Hart is KO’d by his own argument . . . Are we to be horrified by the notion that God consigns anyone finally to hell . . . yet not horrified by the notion that all human suffering and sin, up to and including what we call hell, belongs to the very act of creation?” This, it is fair to say, is an extremely uncharitable take. If there were such an entailment, Hart would have to be a dolt not to see it. By all accounts, he is not. Something else must be going on.

Hart’s repeated emphasis on the eschatological perspective—e.g. “within the story of creation, viewed from its final cause, there can be no residue of the pardonably tragic, no irrecuperable or irreconcilable remainder left behind at the end of the tale” (71-2, emphasis added)—suggests that, on his view, the moral modal collapse is confined to the éschaton. He makes this explicit in his response to John Manoussakis:

my question has nothing to do with contingent evils of any kind; it is rather a very specific query, very clearly delineated, regarding the relationship between God’s ultimate intentionality in creation and the metaphysics of creatio ex nihilo. It is only the final form of creation in its fullness, as judged by God and as either affirming or denying God in turn, that this intentionality is expressed.13

A conscientious critic should take notice and ask, Why does Hart think this? He should then look for an answer in the preceding argument, which is spelled out in the previous twenty pages of the First Meditation.

Before we look at that answer, it might be helpful to get clearer on some terminology.

In general, a modal collapse is the absence of any distinction between necessary and contingent, so that there is only necessity.

God’s antecedent will is his “universal will for creation apart from the fall.” His consequent will is his “particular will regarding each creature in consequence of the fall” (82). Antecedently, God wills eternal beatitude for all. Consequently, he wills eternal punishment for some.

Applied to the distinction between God’s antecedent and consequent will, a modal collapse is the absence of any such distinction, so that whatever God wills, he wills unconditionally.

Applied to the distinction between God’s antecedent and consequent will, a moral modal collapse is the absence of any moral distinction between his antecedent and consequent will, so that he is morally responsible for every possible outcome.

The likes of McClymond and Farrow seem to think that Hart is asserting an unqualified moral modal collapse (or perhaps an unqualified modal collapse). As we have just seen, he is not. Rather, he is asserting a qualified moral modal collapse, a collapse that “occurs” only at the eschatological horizon.

Now, whence the qualification? According to P1-P5, the térma and hence the télos of God’s creative act are identical with the éschaton. If that is right, then God intends the final state of all things.This, P8, is the crux of the argument: God intends the éschaton, all of it, whole and part (The argument has nothing to say about the progression of the cosmos toward its final state, and is in no way committed to the view that God intends historical evils.) In the context of P8, and in response to an anticipated objection (viz., that God intends only one of the many possible éschata), Hart employs an analogy to Agamemnon’s willingness to sacrifice his daughter. The sole purpose of the analogy is to bring out some features of God’s eschatological intention. Just as Agamemnon accepts the possible death of Iphigenia as part of his total endgame, so (on the traditional view) God accepts the possible damnation of persons as part of his total endgame. Put simply, (a) the first half of the argument (if sound) proves that God intends the éschaton; and (b) the analogy (if apt) shows that “the éschaton” includes every possible éschaton. To think that the analogy does any other work is to miss the point.

III. Presumed Premises

1. The Logic of Acts

P2: If a creative act is free of every limitation, its térma is its télos. This is based on an analogy with “human acts” (actus humanus), acts that proceed from a deliberate will, e.g. studying the brush strokes of a painting, running a race, making a pot. As Aquinas observes, “the principle of human acts . . . is the end. In like manner it is their terminus: for the human act terminates at that which the will intends as the end.”14 Consider the act of a potter. The télos of his potting is the finished pot. And the térma of his potting is the finished pot—his potting concludes when the pot is done. So, (assuming there are no mistakes) the goal and terminal state of potting are the same. In this regard, God’s creating is like the potter’s potting.

2. Creation as Eternal Act

P4: The térma of God’s creative act is the éschaton. That is, God’s creating is not finished until every creature has reached its final state. Someone might object:

A potter’s potting is done when the pot has been made, but this is not the pot’s final state. It will end up in a garden, or a museum, or broken and buried. Similarly, God’s creating is done at the end of Day Six or at the Big Bang, but this is not the cosmos’s final state. The Last Judgement is eons down the road. Hence, the térma of God’s creative act is not the éschaton.

This objection takes creation to be an event in time, which is incompatible with classical theism. Here it will be helpful to briefly consider the views of Boethius, Anselm, and Aquinas.

Boethius defines eternity as “the complete, simultaneous and perfect possession of everlasting life.”15 This has consequences for how we think about God’s relation to the cosmos. Boethius focuses on divine “foreknowledge”:

since the state of God is ever that of eternal presence, His knowledge, too, transcends all temporal change and abides in the immediacy of His presence. It embraces all the infinite recesses of past and future and views them in the immediacy of its knowing as though they are happening in the present. If you wish to consider, then, the foreknowledge or prevision by which He discovers all things, it will be more correct to think of it not as a kind of foreknowledge of the future, but as the knowledge of a never ending presence.16

It is as if God occupies a place outside of time and, from that perspective, sees the past, present, and future all at once. Accordingly, the future is present to Him in something like the way the present is to us.

Anselm adopts Boethius’s definition of “eternity”—“[the perfect substance’s] eternity is life unending, simultaneous, whole, and perfectly existing,”17—and understands this to mean that God is timeless:

Or is there nothing past in Your eternity, so that it is now no longer; nor anything future, as though it were not already? You were not, therefore, yesterday, nor will You be tomorrow, but yesterday and today and tomorrow You are. Indeed You exist neither yesterday nor today nor tomorrow but are absolutely outside all time.18

[I]t is necessary that [the supreme substance] be present as a whole simultaneously to all places and times, and to each individual place and time.19

Like Boethius, Anselm thinks of God as “outside” of time and, therefore, simultaneously present to every moment in the past, present, and future. And he grounds divine foreknowledge in this eternal presence. But additionally, Anselm sees a connection between God’s knowing and his creating: “When God wills or causes something, he cannot be denied to know what he wills and causes or to foreknow what he is going to will and create.”20 He foreknows what he is going to create. Or rather—since “‘foreknowledge’ . . . [is] not used of God literally, for in him there is no before or after, but all things are present to him at once”21—he knows and creates everything, at every time, all at once.

Aquinas also accepts Boethius’s definition of eternity,22 and with Anselm, sees its implications for both knowledge and creation:

since God’s act of understanding, which is His being, is measured by eternity; and since eternity is without succession, comprehending all time, the present glance of God extends over all time, and to all things which exist in any time, as to objects present to Him.23

God is the cause of things by His knowledge . . . His knowledge extends as far as His causality extends.24

If God causes the existence of things by his knowledge, then his knowledge and his causality are coextensive. Consequently, if his eternally present knowing extends over all time, to all things which exist in any time, his eternally present creating extends over all time, to all things which exist in any time. That is, his creative act comprehends all time.

Hart is in agreement with this theological tradition. He does not spell it out, but his language subtly invokes it:

And this eternal teleology that ultimately governs every action in creation, viewed from the vantage of history, takes the form of a cosmic eschatology. Seen as an eternal act of God, creation’s term is the divine nature for which all things were made; seen from within the orientation of time, its term is the “final judgment” that brings all things to their true conclusion. (69, emphasis added)

God is eternal, and therefore, His creative act is an eternal act. As such, it is the simultaneous creation of the entire temporal order, archē to éschaton. Hence, the éschaton is directly created by God. And since it is, by definition, the final state of the cosmos, it must be the térma of God’s creating. For Hart, this final state is, from God’s eternal perspective, the divine nature, i.e. the creaturely participation in the divine nature; and from our temporal perspective, it is the future Last Judgment.

IV. For the Greater Good

On Wahlberg’s view, a greater good response succeeds against Hart’s moral modal argument:

how can Hart rule out the possibility that there is some immense good that is incompatible with universal salvation, and that God reasonably wills more than he wills universal salvation? The answer is, of course, that he cannot. At most, Hart can argue that it does not matter how great any suggested ‘greater’ good is, since it would in any case be morally bad (and hence impossible) for God to purchase it at the expense of the final loss, or even the possible loss, of a single soul. It follows from this that God is morally bound to prevent such loss at any cost, and hence to forfeit any good—however great—that conflicts with universal salvation. (“The Problem of Hell,” 50)

“At most,” Hart can argue that it would be morally evil and hence impossible for God to intend the final loss of a single soul as part of His intention to bring about some greater good, say, “friendship or intimacy with God” (“The Problem of Hell,” 55). In other words, at most, Hart can argue that God would have to intend a relative evil in order to intend a relative good. But this is obviously sufficient. And it obviously rules out the possibility that Wahlberg wants to defend.

Benjamin Guyer, “David Bentley Hart has Written a Silly Book,” The Living Church, November 10, 2019: https://livingchurch.org/covenant/david-bentley-hart-has-written-a-silly-book/; Edward Feser, “David Bentley Hart’s attack on Christian tradition fails to convince,” Catholic Herald, July 10, 2020: https://catholicherald.co.uk/david-bentley-harts-attack-on-christian-tradition-fails-to-convince/; Denys Kondyuk, “David Bentley Hart. That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell and Universal Salvation,” Theological Reflections Eastern European Journal of Theology, May, 2020: http://reflections.eeit-edu.info/article/view/203374; Joshua R. Brotherton, “That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation by David Bentley Hart,” Nova et Vetera, Fall 2020; Taylor Patrick O’Neill, “That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation by David Bentley Hart,” Nova et Vetera, Fall 2020.

Alan W. Gomes, “Shall All Be Saved? A Review of David Bentley Hart's Case for Universal Salvation,” Credo Magazine, December 2, 2019: https://credomag.com/article/shall-all-be-saved/; Benjamin B. DeVan, “Shall All Be Saved? David Bentley Hart’s Vision of Universal Reconciliation—An Extended Review,” Christian Scholar’s Review, November 12, 2020: https://christianscholars.com/shall-all-be-saved-david-bentley-harts-vision-of-universal-reconciliation-an-extended-review/; James Dominic Rooney, “The Incoherencies of Hard Universalism,” Church Life Journal, October 18, 2022: https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/the-incoherencies-of-hard-universalism/

Michael McClymond, “David Bentley Hart’s Lonely, Last Stand for Christian Universalism,” The Gospel Coalition, October 2, 2019: https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/reviews/shall-saved-universal-christian-universalism-david-bentley-hart/; Douglas Farrow, “Harrowing Hart on Hell,” First Things, October, 2019: https://www.firstthings.com/article/2019/10/harrowing-hart-on-hell

Mats Wahlberg, “The Problem of Hell: A Thomistic Critique of David Bentley Hart’s Necessitarian Universalism,” Modern Theology, September 9, 2022: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/moth.12816

David Bentley Hart, “A Pakaluk of Lies,” First Things, February 14, 2020: https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2020/02/a-pakaluk-of-lies

David Bentley Hart, “The obscenity of belief in an eternal hell,” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, June 13, 2022: https://www.abc.net.au/religion/david-bentley-hart-obscenity-of-belief-in-eternal-hell/13356388

David Bentley Hart, “A Response to Benjamin B. DeVan,” Christian Scholar’s Review, November 12, 2020: https://christianscholars.com/that-all-shall-be-saved-a-response-to-benjamin-b-devan/

Hart, “The obscenity of belief in an eternal hell.”

In several replies (see Notes 6, 7, 10, and 13), Hart restates parts of the argument. Unfortunately, these are unlikely to help someone who did not understand the First Meditation.

David Bentley Hart, “The Edward Feser Algorithm (How to Review a Book You Have Not Read),” Eclectic Orthodoxy, July 21, 2020: https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2020/07/21/the-edward-feser-algorithm-how-to-review-a-book-you-have-not-read/

See Thomas Belt, “God’s Eschatological Salvific Will: Revisiting Hart’s Moral Argument for Universalism,” Eclectic Orthodoxy, February 13, 2023: https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2023/02/13/gods-eschatological-salvific-will-revisiting-harts-moral-argument-for-universalism/; and Aidan Kimel, “The Premises of the Moral Argument Against Hell,” Eclectic Orthodoxy, February 19, 2023: https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2023/02/19/the-premises-of-the-moral-argument-against-hell/

This is confirmed by Hart’s comments in “What God Wills and What God Permits”: “It is a logical truism that all secondary causes in creation are reducible to their first cause. This is not a formula of determinism. It merely means that nothing can appear within the “consequents” of God’s creative act that is not, at least as a potential result, implicit in their primordial antecedent. So, even if God allows only for the mere possibility of an ultimately unredeemed natural evil in creation, this means that, in the very act of creation, he accepted this reality—or this real possibility—as an acceptable price for the ends he desired. . . . And so, if God does indeed tolerate that final unredeemed natural evil as the price of his creation . . . he also converts that natural evil into a moral evil, one wholly enfolded within the total calculus of his own venture in creating.” Notice that the relevant “consequents” are “ultimately unredeemed natural evil[s] in creation,” “final unredeemed evils.”

David Bentely Hart, “Manoussakis and his Pear Tree,” Eclectic Orthodoxy, November 17, 2019: https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2019/11/07/manoussakis-and-his-pear-tree/

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I-II, Q. I, A. 3, Corp.

Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy, Bk. V, Ch. VI.

Ibid.

Anselm, Monlogion, Ch. 24.

Anselm, Proslogion, Ch. 19.

Anselm, Monologion, Ch. 23.

Anselm, De Concordia, Bk. 1, Ch. 4.

Ibid., Bk. 2, Ch. 1.

Aquinas, Summa I, Q. 10, A. 1, Corp.

Aquinas, Summa I, Q. 14, A. 9, Corp.

Aquinas, Summa I, Q. 14, A. 11, Corp.

Thank you for this Bradford.

I don’t disagree with Hart’s moral modal argument. As a universalist I’ve defended it. I think it’s irrefutable.

I would suggest however that your P13 as stated is false. 'Irrevocable' suffering as a final state – yes, that’s the problem. But clearly (clearly enough to me) not all suffering is evil. Some transient suffering can be instrumental, redemptive, therapeutic, pedagogical. So if P13 means ‘suffering’ simpliciter, I'd see that as a problem. At the very least, the distinction I'm suggesting doesn't undermine the moral argument.

Tom

Bradford, this is Fr. Rooney. I responded two years ago to Hart's argument on Facebook, offering a similar reconstruction to that you propose (although much more streamlined and logically perspicuous) and noting that the first premise is unmotivated and ought to be rejected. In your reconstruction, I believe that roughly corresponds to rejecting premise 15. It does not follow that, if someone is eternally damned, God directly wills rather than merely permits their damnation.

In addition to that chief logical move to reject the argument's conclusion, I'd reject premise 13. Suffering is not an intrinsic but an accidental evil and so it does not follow that if God intends suffering He intends a per se evil. Further, I think many of the claims made about the eschaton are likewise false and rely on equivocation, but I don't see that they prove much in the way of supporting that premise 15.

You can find my recent resharing of that post, but there were a few others in this series.

https://www.facebook.com/share/p/16Tao5Rxez/